Battle for the locks

Overzicht van de gevechten die plaats hadden tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog aan de Kempische Kanalen

Overview of the battles that have taken place during the Second World War besides the Escaut Canals

Geel - Ten Aard

Lt. John Ray Stobo

CDN228

Jack Stobo just after the war

Foto © GG

Canloan officier

Lt. John Stobo, Jack Stobo was a CANLOAN officer on loan to the British Army, 15th Scottish Division, from May, 1944 to December, 1945, when he returned to Canada after the end of the war. He fought in all of the major battles in Northwest Europe, including the battle of Normandy (D-Day + 10), Battle of the Gheel Bridgehead at Gheel, Belgium, Battle of Best, Netherlands, and finally various smaller battles in Northwest Germany. He joined the Canadian Army in 1936 before the war, and he actually ended up as a Sergeant in an anti-aircraft unit which was stationed in Iceland, of all places. There wasn’t much action going on there in Iceland, and he wanted to see some action, so he was selected and he decided to volunteer for a junior officer training program back in Canada. After a short 3-month officer training program back in Canada, he was subsequently posted back to England under the CANLOAN OFFICER SCHEME, as a 2nd lieutenant, CDN 228, on loan to the British Army, 15th Scottish Division, 44th Brigade, 8th Battalion Royal Scots. He ended up as leader of 12th platoon in B Company. My dad was a very professional soldier right from the start, which probably helped him to survive all of the heavy fighting that he was involved in in France, Belgium, Netherlands, Germany.

Here are his personal experiences of the Aard battlefield:

CROSSING THE SEINE AND INTO BELGIUM

On the 27th of August, as we approached the Seine River, the CO received orders to

take the Battalion across that night in assault boats. The decision to cross without delay

put a severe strain on the administrative machinery, as boats had to be provided,

and brought forward, forming up places established, and numerous other details settled.

At Porte Joie, the Seine was nearly three hundred yards wide. Beyond the opposite bank,

where the hills overlook the river, the enemy had an excellent defensive position.

The Battalion would have to cross, without having a chance to recce the embarkation point,

or even see the opposite bank, where we had to land, as it would be dark long before

we reached the assembly area.

The Royal Scots Fusiliers had already crossed at a different place, and had met with

enemy opposition. It was a dismal rainy night, and a heavy mist lay on the water, but

the current was slight, and our assault boats made good progress. As we paddled across,

I remember feeling the water. It was so warm I had almost been tempted to plunge in

for a swim. We reached the far bank, and scrambled up to the top of the hill, where we dug in,

without having to fire a shot, or without suffering a single casualty in the crossing.

The next few days were spent rounding up pockets of enemy resistance in the

Foret de Bacqueville. Our Battalion cooks, left behind to prepare an evening meal,

rounded up three of the enemy. When our transport finally arrived, we continued our

mobile advance, and by the 5th of September, we had crossed the Somme River, and

passed St. Pol, one of the places from which V-1 flying bombs had been launched on Britain.

“Hell bent for leather”, we moved through industrial northern France to the Belgian frontier

and on to the town of Halluin, Belgium.

Our welcome in Northern France had been exciting, but it was nothing compared to the welcome

we received in Belgium. The Belgians were hysterical with joy, and were most hospitable,

offering us fruit and flowers when we had to halt, because of the crowds of well-wishers.

We later arrived in Courtrai amid scenes of great enthusiasm.

We could see the Germans withdrawing towards the Scheldt. Continuing our pursuit,

we picked up about sixty prisoners, but met no real opposition. On the 10th of September, 1944,

we arrived at Malines, midway between Antwerp and Brussels, after a day’s journey of

seventy-five miles. Our glorious few days were soon to end, as the following day,

the 15th Scottish Division was ordered to clear the enemy from the area between

the Albert and Meuse-Escaut Canals, and to establish a bridgehead over the Escaut Canal.

ACROSS THE ALBERT CANAL

After crossing the Albert Canal, my company was in the process of taking over a position

from a company in another Battalion, when the enemy counter-attacked with infantry,

supported by artillery. Before we reached the position, a rifle grenade exploded between

a corporal and myself, severing his jugular vein, and wounding several others.

I was fortunate in receiving only small fragments in my abdomen from some of the blast,

and was able to continue feeling only some numbness in my stomach.

During the counter-attack, we had to relieve the other platoon, slit trench by slit trench.

I also recall that during this period, solid shot from a German 88 mm gun was sending

rounds through the brick wall of the house I was standing beside. I was relieved that they had

not been high explosive rounds.

Some time after we had completed the take-over, I discovered in the basement of

the damaged house in our area, about forty civilian women, children and a few elderly men.

They appeared relieved when the firing had ceased, and they were able to come out.

I still recall how clean they looked. Their shelter was also clean with fresh straw.

Their appearance would have made them acceptable at any church service. After leaving this position

as part of XII Corps, the 15th Scottish Division was given the task of opening

up the bridgeheads across the Meuse-Escaut Canal. Our 44 Brigade moved north towards Gheel.

AART - THE GHEEL BRIDGEHEAD - ACROSS THE ESCAUT CANAL

Part of Montgomery's plan, of which we knew nothing at the time, was to move through Holland, and

then swing eastward across the Rhine into Germany, and, with a left hook through Hamm, cut off the Ruhr.

The first stage of this advance was the capture of three important bridges

that crossed the Maas at Grave, the Waal at Nijmegen, and the Lower Rhine at Arnhem.

In this operation, known as “Market Garden”, some 35,000 airborne troops were to be dropped

to seize the bridges in these places, and XXX Corps, commanded by Gen. Horrocks, was to

push forward to join up with them. In order to protect the left flank of XXX Corps, XII Corps was

to cross the canal and hasten north on the west flank, while VIII Corps would do the same on

the east flank. By the 12th of September, XXX Corps had crossed the Meuse-Escaut Canal in the vicinity of Neerpelt,

and were precariously holding a small bridgehead. From there, they were to push northward,

in an effort t reach Arnhem on the third day of the operation to link up with

the airborne troops. The 44 Brigade, consisting of the 8th Royal Scots, the 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers,

and the 6th King’s Own Scottish Borderers, were ordered to go forward to Gheel,

a village which had previously been captured by 50th Northumbrian Division but

subsequently lost.

The factory on the north side of the canal in September 1944. Picture © GG

The 8th Royal Scots sent strong fighting patrols forward in the early morning of the

14th of September, and took a number of prisoners. They found that the main body

had withdrawn. A couple of miles north of Gheel was the Escaut Canal. The road to Turnhout crossed

it at the small village of Aart. The Royal Scots were ordered to carry out an assault crossing of the

Escaut Canal that night in darkness, using assault boats and, once again, no time for daylight recce was possible.

The road and footbridge across the canal to the village of Aart had been destroyed, and the enemy was

holding the village and surrounding area.

Just before dawn, we crossed the canal in our assault boats, with only slight enemy fire,

although we lost one man and a LMG Bren. Our crossing was made about six hundred yards

to the west of the village of Aart. Two of our companies were to swing east and clear the village,

while my company was to go north beyond the village and hold the open left flank.

We met with enemy resistance from the wooded area to our front and on our left flank.

An enemy sniper, firing from a brick house in the woods was silenced by a direct hit

from our PIAT anti-tank weapon. A German self-propelled 88 mm gun, concealed in the woods

to our front, was causing some problems by firing and frequently changing position.

We had taken several prisoners, who were typical Hitler youth. They were arrogant and had

to be held in our own position, as it was out of the question to

send them to the rear. Although we had several casualties from enemy shelling, these

cocky prisoners refused to dig any shelter for themselves, or to share the protection of our slit trenches.

Meanwhile, our other three companies, engaged in clearing the village, and our east flank,

had also run into stiff German counter-attacks. They were forced to retire to the canal bank after

German tanks had broken through.A number of their positions were overrun, and several of their

detachments were cut off. One of our company Headquarters was surrounded. When the enemy

broke into their position, the Coy commander and two other officers and surviving members of

the Headquarters were taken prisoner. The enemy attack on D” Coy began with a platoon commanded

by Canloan Officer Lt. Jackson Stewart. He was killed by a grenade in hand-to-hand fighting,

and many of his men also died behind their weapons. German shelling on the bridge site prevented

our engineers from making any progress on bridge construction. It was therefore, impossible to

get any supporting arms across to us. Assault boats were being punctured by the shelling,

and small arms ammunition had to be ferried across to us.

Our bridgehead was reduced to about 50 yards wide and fifty deep with German tanks, SP guns,

and infantry milling about in our Battalion areas. With the situation now critical on the

open east flank, and in the village, the CO ordered my “B” Coy to withdraw to the village

to restore the small bridgehead, and clear the enemy from the village. In darkness, during

the night, with the enemy on either side of us, and between us and the rest of the Battalion,

we moved back in single file in complete silence. The enemy probably thought we were their

own infantry advancing. German tanks were about, and straw stacks and village homes were ablaze.

When we reached the village, we moved up the main street, clearing the enemy who had

managed earlier to re-enter it. LMG Brens and riflemen were firing continuously.

By dawn, we were still holding the village and our small bridgehead. Heavy German shelling

continued on the village and the bridge site. Still no progress had been made on the construction

of the bridge. German counter-attacks continued with their attempts to get back to the village.

We managed to hold them off with sustained small arms fire, and a German antitank gun, which

they had left behind when we cleared them from the village. Fortunately, they had also left a good

supply of ammunition for it, although they had taken the sight. With the help of a couple of my men,

we were able to get the weapon firing by levelling the barrel, and firing down the main street of the

village at the enemy attempting to re-enter from the north end, and at houses where we had seen

enemy entering. This appeared to lead them to believe that we had been able to get anti-tank weapons

across the canal and, therefore, cooled them down for a time.

There was no thought of sleep in this operation with enemy counter-attacks continuing throughout.

Just before dawn on the third day, a German NCO approached our forward platoon speaking in good

school-boy English, “Come on Tommy, surrender, you are surrounded.”

I had one of my Bren gunners answer him with a good burst, which appeared to eliminate him in short order.

During the third day, we could hear German track vehicles forming up in the woods for another counter-attack.

I requested an artillery concentration on the area, and was able to relay corrections of the first salvo back to

Coy Headquarters for transmission to the Battery Commander. We received immediate support, and a heavy

concentration on the area produced screams from the enemy for stretcher bearers, and discouraged any further attempt at

counter-attack at this time. Attempts b enemy infantry to come in on our left flank were

also warded off by use of our 2in mortar.

Finally, on the 15th of September, around noon, the 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers crossed the canal to go through us,

and attempt to expand the bridgehead. A few hours later though, a heavy German counter-attack came in down

the main road from Turnhout, causing them to quickly withdraw back through our position on the main road,

leaving us again in the same exposed position. I found this RSF withdrawal somewhat amusing as when they had

earlier moved forward through our position, one of their cocky jocks rudely commented, :What’s holding you up,

we will show you how it’s done.” At about 8:00 p.m. that day, the 6th KOSB of 44 Brigade was ferried across the canal and

squeezed into position in our sector. This was now our fourth day in the bridgehead without having any food or sleep.

The Brigadier had ordered that we were to be withdrawn that evening. However, the CO’s of the RSF and KOSB asked our

CO to keep his men in the bridgehead for the time being. The Brigadier agreed, and decided that, with the 8th Royal Scots

forming a firm base, the 6th RSF and 6th KOSB would launch an attack at dawn the next day,

the 16th of September, to try once again to expand the bridgehead.

While they were preparing to launch their attack, the enemy lashed in with an attack of tremendous force, upsetting

the whole balance of the operation. The RSF and KOSB were unable to get across their start line. We, therefore had to

continue holding our small bridgehead until the next day, which was the 17th of September.

At about 7:00 a.m. that day, they started ferrying our Battalion back across the canal, with my company being the last to leave.

Our casualties for this operation were ten officers and one hundred and eight other ranks.

After being relieved in the bridgehead, we returned to the village of Gheel, where food and clean clothing was available.

After four days without food or sleep, except for eating our emergency rations, consisting of a small bar of chocolate

on the second day, our first gourmet meal served to us was a tin of like-warm pork and vegetables. This did not really tickle our taste buds.

However, we were all so tired we could not have appreciated food at that time anyway.

While we remained in Gheel, we saw the sky full of planes and gliders as the British 1st Airborne was on its way to Arnhem.

Before leaving Gheel, I took another look at our embarkation point for crossing the Escaut Canal. I discovered some documents

belonging to another Canloan officer, Cdn 233 Lt. Ken Coates. He was killed with the 6th KOSB at the same crossing point

we had used four days earlier. I also found where one of my Bren gunners had been killed at the same place and why

we had been missing one Bren after the crossing.

Although the 8th Royal Scots received a battle honour for our fighting in the Gheel Bridgehead,

it might have been considered a failure since it ended with the 227th Brigade relieving

our Brigade, and we were pulled back across the canal with the enemy in possession

of the shattered village of Aart. However, many troops had to be deployed by the Germans

to deal with the bridgehead, thereby relieving some of the pressure on Gen. Horrocxk’s

XXX Corps that was attempting to reach Arnhem. The Guards Armed Brigade that was spearheading XXX Corps reached

Eindhoven and Nijmegan, but failed to reach Arnhem and link up with the 1st Airborne.

Lt. Stobo receives the Military Cross fromGeneral Montgomery Weddingpicture. His wife serverd the Canadian army as a nurse

Foto © GG Foto © GG

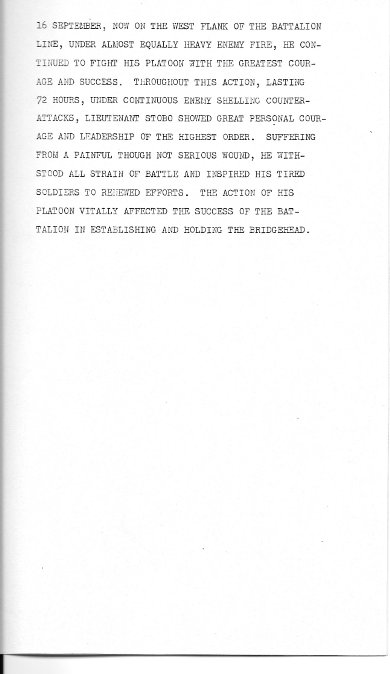

Why he received the Military Cross

© GG